Young adult authors are breathing new life into the heroines of ancient Greek tales

Hercules. Achilles. Perseus. Odysseus.

You’d be hard-pressed not to recognize the names of these famous Greek heroes. Stories of their adventures stretch far and wide across time, immortalizing them in our books, on our TV screens and within our cultural memory. And yet, one can’t help but ask: where are the heroines?

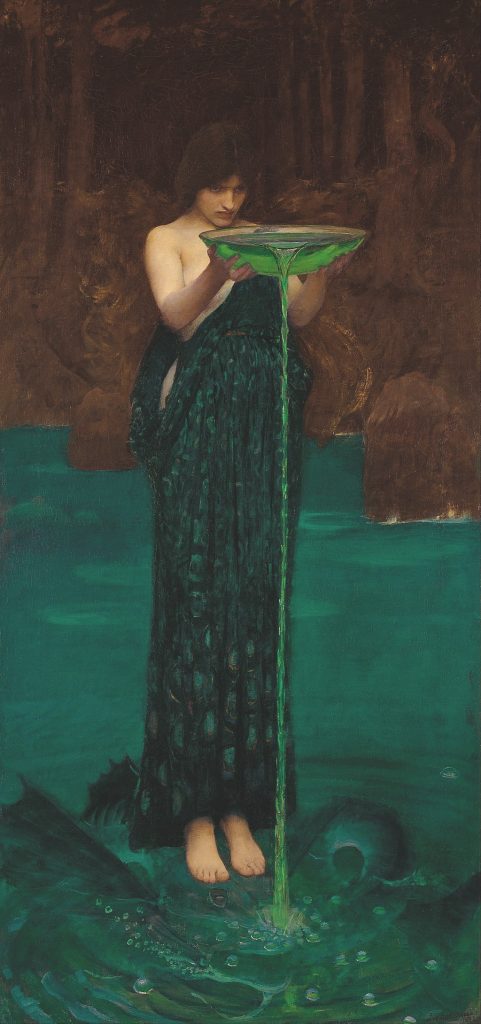

For centuries, women have appeared in ancient Greek tales as sinister threats or objects of sexual desire — conquests and little more. Rarely have they appeared as protagonists in their own right. Rather, these traditional stories, largely written by men, have stifled their narratives and relegated them to the shadows. “The few women who appear are there mostly as cameo helpmeets, breeding stock, or obstacles to be overcome,” observes Circe author Madeline Miller. “Their stories only matter in how they touch the hero’s.”

Miller is one of a number of young adult writers who are helping to “flip the script,” as she puts it. Feminist retellings of Greek myths are seeing a surge in popularity, with not only Miller’s Circe but a host of other novels — Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls, Natalie Haynes’s A Thousand Ships, Jennifer Saint’s Ariadne and Jessie Burton’s Medusa — making waves in the YA market over the past five years. This trend emerged in the mid-2000s when writers such as Margaret Atwood and Ursula K. Le Guin began reimagining ancient stories from the perspectives of famously overlooked women. Atwood’s The Penelopiad features Penelope and her maids rehashing the events of the Odyssey, while Le Guin’s Lavinia gives voice to the silent princess in Virgil’s Aeneid. “If I must go on existing century after century, then once at least I must break out and speak,” Lavinia reflects in the novel.

Sarah Underwood’s Lies We Sing to the Sea is the latest addition to this collection of Greek mythical retellings from a feminist lens. Releasing in early March, Underwood’s literary debut is a self-described “sapphic feminist reclamation” set 300 years after the events of the Odyssey. Like Atwood’s book, it picks up a single neglected thread within the ancient tale: Penelope’s 12 maids.

To understand the premise of the story, we must first look to Odysseus himself. After a decade-long journey, Odysseus returns home from the Trojan War to find his devoted wife, Penelope, pursued by more than 100 suitors — all convinced of his death and pressuring her to remarry despite her efforts to stall them. Naturally, Odysseus kills them all with the help of his son, Telemachus. He then sets his sights on Penelope’s maids, believing them disloyal due to their sexual involvement with the suitors. So he orders Telemachus to execute them — after they’ve cleaned up the bloody mess.

This brings us to the events of Underwood’s adaptation, in which the maids were not willing participants in the suitors’ advances but victims of sexual assault. Through Odysseus’s ruthless call, the hanging of the 12 innocent maids incites a snowball effect that plagues the city of Ithaca for hundreds of years to come. As it happens, the maids were devoted worshippers of the sea god Poseidon. Since Poseidon already held great contempt for Odysseus, he curses the kingdom so that a sacrifice of 12 women must be ordered by its ruler each summer — or else Ithaca itself would be drowned. And his price to end this curse? Twelve men from Odysseus’s royal line. Twelve men for the 12 maids.

If that isn’t poetic justice, the ones who would give Poseidon those men were the hanged women themselves. Twelve women chosen among the thousands dead, resurrected over time by Poseidon and sent as immortal shape-shifting, water-bending sea creatures to exact their revenge.

The events of the book take place at the tail end of this curse. Leto awakens after her hanging to find herself on the island of Pandou, a liminal place. She meets the beautiful Melantho, whom readers might recognize as the only maid mentioned by name in the Odyssey. While she is characterized as a sharp-tongued, ungrateful traitor in the original tale, Underwood’s Melantho is world-weary and deeply traumatized. Bound to the island alone for hundreds of years, she tearfully receives and buries the hanged bodies that wash up on her shores while awaiting the arrival of Poseidon’s next chosen one. When they appear, she must train them to use their powers and send them off to commit their assassination alone.

Leto is the 12th and final chosen one — and Prince Matthias, who was there to order and witness her hanging, is the final male royal in 12 generations of his line. Vengeful and furious, Leto manages to get Melantho off her island prison, and they both embark on a mission to see the prince killed and the curse lifted. What follows is an adventure filled with conflict, romance and hidden secrets that significantly complicate what should have been a simple task.

In this book, Underwood does exactly what makes feminist retellings so gripping. She joins the new (the wilful and defiant Leto) with the old (the hurt and misunderstood Melantho) in a story that is equally compelling to those familiar and unfamiliar with the source material. She even refers to many of the original 12 maids by name, a luxury they were never granted before.

While Underwood has faced criticism for admitting that she has never read Homer’s Odyssey in its entirety, her care and respect for the traditionally marginalized female point of view is evident in every chapter of this story — and the result is women who are complicated, endearing and delightfully relatable. By contrast, the noblemen depicted in the Odyssey (Odysseus and Telemachus, as well as the suitors Antinous and Eurymachus) are reduced here to cruel faces in Melantho’s nightmares.

Perhaps this is what readers find so compelling about women-centric retellings. How might the maids, the wives, the oracles and the witches have seen the men so often lauded in Greek tales? Their views of the heroes may well be less flattering.

Odysseus, for example, is usually shown as clever and cunning in Greek myth, but rarely as a vicious liar who has committed adultery on at least two occasions — turns out, Penelope’s years of devotion were not reciprocated.

She isn’t the only one to have her husband act against her. Unfortunately, Hercules’ love story with Megara doesn’t have the happy ending we’ve come to know from the beloved Disney animated movie. Instead, versions of his story (notably from Euripides) show him driven to a violent rage by Hera, the queen of the gods, that results in him killing both Megara and their children, either by arrows or burning them alive.

And what of the brave Achilles, who kidnaps Briseis after slaughtering her family, taking her as his personal slave and concubine? Or Perseus, who beheads Medusa in her sleep after she was raped and cast away, then uses her head to kill far more people than she ever did while alive? The sins of the heroes are often glossed over while women pay the price.

Female suffering is an age-old commodity that has, frankly, gone stale. Readers are tired of stories that treat women as collateral damage or spoils of war. To paraphrase Underwood, people want to read books in which a thousand ships are launched not for women, but by them. They want to explore these characters’ dreams, their labours, their unique madness and righteous vengeance.

So forget the heroes. Think about Penelope, Melantho and the 11 nameless maids. About Megara, Briseis and Medusa. The heroines of their own stories, at last being written.

Source : Broadview