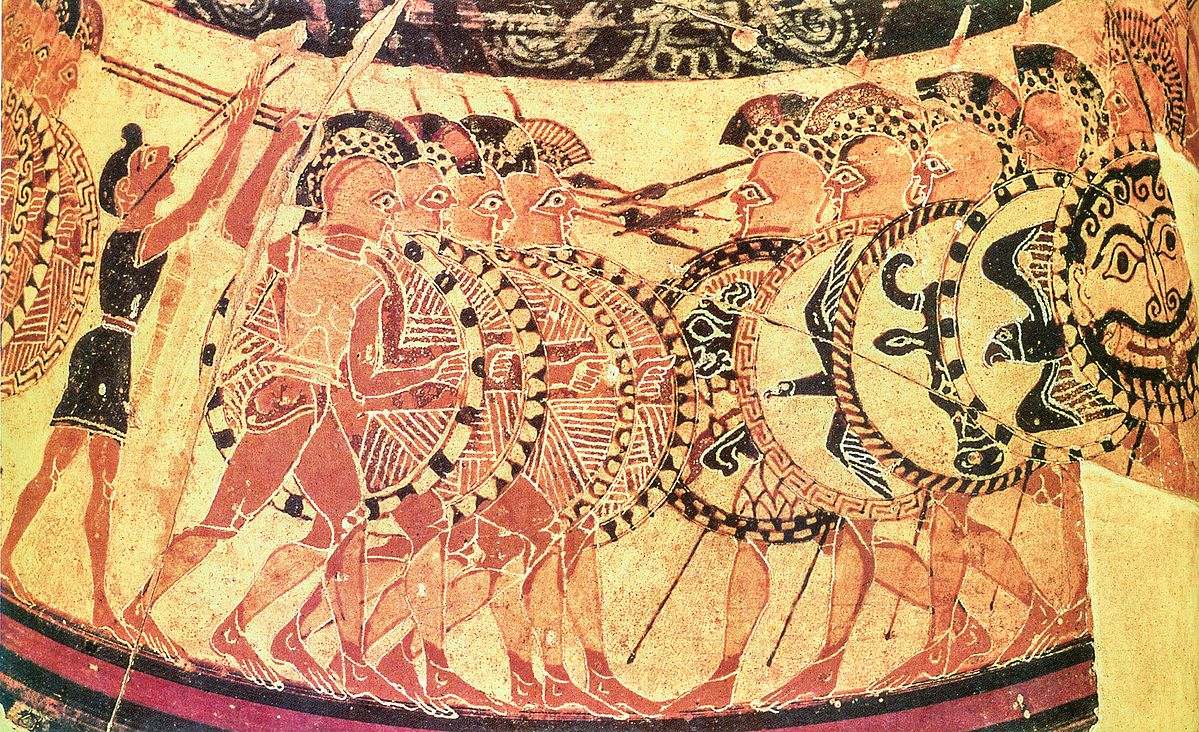

With the Wagner Group security crisis currently unfolding in Russia, mercenaries are all over the news, but soldiers for hire are nothing new; in fact, they were ubiquitous across the ancient Greek world.

More often than not, the citizen-soldier hoplite armies of the ancient Greek city states or the professional Macedonian armies of Philip II and Alexander the Great tend to take the limelight in historical discussions. However, mercenaries were a very common sight on the battlefields of ancient Greece.

Other civilizations were keen to hire ancient Greek mercenaries who could fill a variety of important roles in their armies. For example, hoplites-for-hire were prized for their expertise as heavy infantry, whereas Cretan archers were sought after for their skill at ranged combat.

Soldiers of fortune

There is evidence going as far back as the Bronze Age that the inhabitants of Greece took up arms as soldiers for hire. For example, Papyrus fragments from El-Amarna in Egypt, dated to the second half of the 14th century BC, appear to show a Mycenaean warrior wearing an iconic boar tusk helmet. The depicted warrior may have been a Mycenaean mercenary in service to the 18th Dynasty of Egypt.

During the Archaic period, more evidence emerges of Greek mercenaries finding employment across the southeastern Mediterranean. Greek aristocrats are known to have fought in the army of the Neo-Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II during his campaign to capture Ashkelon in 601 BC.

During the Classical and Hellenistic periods, Greek mercenaries were a common sight in battles across the Mediterranean. According to an academic paper written by Harvey F. Miller, there was an “explosion” in the number of ancient Greek mercenaries in the 4th century BC.

Historians have proposed many reasons for the ubiquity of Greek mercenaries in the ancient world. Some may have been driven by poverty or problems associated with overpopulation in their homelands, whereas others may merely have been desirous of adventure and riches. Naturally, the context varied over time. For example, there was ample demand for mercenaries because of the political instability that ensued after the death of Alexander the Great.

Xenophon and the Ten Thousand

The most famous ancient Greek mercenaries were the Ten Thousand whose story was immortalized in the accounts of the Greek philosopher, historian, and military commander Xenophon.

In 401 BC, Cyrus the Younger employed 10,000 mercenaries, mainly from Greece, to help him seize the Persian throne from his brother Artaxerxes II. At the Battle of Cunaxa, the Greek mercenaries proved their worth and routed the enemy lines. However, they discovered after the battle that their employer Cyrus had been killed, rendering their victory pointless.

Without an employer, adequate food supplies, or local allies, the Ten Thousand were trapped deep behind enemy lines within the Persian Empire. Despite the odds, they made it back to Greece in 399 BC. After years of fighting, the mercenaries are said to have exclaimed “Θάλαττα! θάλαττα!” (“The sea! The sea!) when they made it to the coast.

Other famous ancient Greek mercenaries

Xenophon and the Ten Thousand were not the only ancient Greek mercenaries to have made a name for themselves in antiquity.

Hybrias, a Cretan mercenary and lyricist of the 6th century BC, popularized a drinking song of his own composition. His “spear-song” is translated thus:

I have great wealth –

a spear, a sword and a fine shield

to save my skin.

With these I plough, I reap,

I tread the sweet grapes

and am called master of my serfs.

All those that dare not hold

the spear and sword

and fine shield to save their skin,

all bow and kiss my knee,

calling me master

and great king.

The Cretans in general were famed across the Mediterranean as exceptionally gifted archers. They wielded composite bows with a wooden core and laminated layers of sinew and horn which afforded them greater range than their adversaries. Additionally, both Xenophon and Aristotle recorded that the Cretan archers carried bronze-covered small circular shields that would have offered them some protection if they had to fight up close or if they were shot at by enemy missile troops.

Some Spartans also made a name for themselves as mercenaries. The most well-known was Xanthippus of Lacedaemon who reformed and commanded the Carthaginian army during the First Punic War. His tactical brilliance was largely responsible for the Carthaginian defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Tunis in 255 BC.

Source: Greek Reporter